When a doctor gives a patient a biosimilar drug like Inflectra or Renflexis instead of the brand-name Remicade, the billing process isn’t as simple as handing over a generic pill. Unlike traditional generics, biosimilars don’t get lumped into one code and paid the same rate. Each one has its own billing code, its own payment rate, and a complex set of rules that determine how much the provider gets paid-and why that matters for both patients and providers.

How Biosimilars Are Different From Generics

It’s easy to think of biosimilars as just cheaper versions of biologic drugs, like how generic aspirin is to brand-name aspirin. But that’s not accurate. Biologics are made from living cells-complex proteins that are hard to replicate exactly. Biosimilars are highly similar, but not identical. That’s why the FDA treats them differently than small-molecule generics. And Medicare treats them differently too. Generics have an AB rating. If a drug is AB-rated, pharmacists can substitute it automatically. Biosimilars don’t have that. Even if they’re approved as biosimilar, they’re not automatically interchangeable unless the FDA gives them an "I" designation. And even then, insurance rules and provider habits often block automatic switching. This complexity shows up in the billing system. Instead of one code for all biosimilars of a drug, each one gets its own unique HCPCS code. That’s a big shift from what happened before 2018.The 2018 Reimbursement Change: Why It Happened

Before January 2018, all biosimilars for the same reference product-say, infliximab-shared one HCPCS code: Q5101. CMS paid providers based on a blended average of all the biosimilars on the market. So if one company priced its biosimilar low, everyone else got a free ride. Why invest in a cheaper product if you’re paid the same as the more expensive one? That system discouraged new biosimilar entry. Manufacturers had little incentive to bring down prices because their reimbursement didn’t reflect their actual cost. The result? Fewer competitors, slower price drops, and less savings for Medicare. In 2018, CMS flipped the script. Now, every FDA-approved biosimilar gets its own product-specific code. Inflectra has J7322. Renflexis has J7323. Each gets paid based on its own Average Selling Price (ASP), plus a 6% add-on based on the reference product’s ASP. This change fixed the "free rider" problem. Now, if a biosimilar is cheaper, the provider gets paid less-but the patient pays less too. And the manufacturer can compete on price without being penalized.How Payment Is Calculated

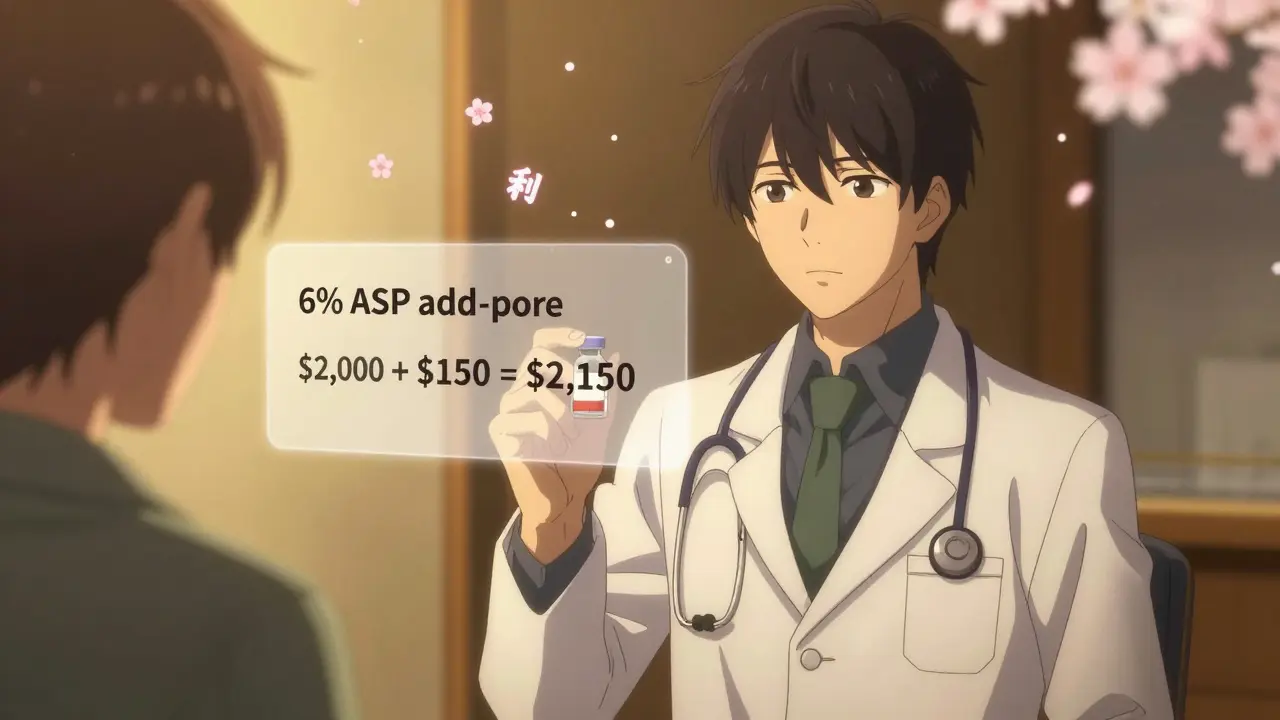

Here’s how the math works for a typical biosimilar under Medicare Part B:- Payment = 100% of the biosimilar’s individual ASP + 6% of the reference product’s ASP

- Inflectra’s payment = $2,000 (100% of its ASP) + 6% of $2,500 ($150) = $2,150

HCPCS Codes: J-Codes and Q-Codes

Every biosimilar gets a unique HCPCS code. These are either J-codes (permanent) or Q-codes (temporary, used while data is being collected). For example:- J7322 = Inflectra (infliximab-axxq)

- J7323 = Renflexis (infliximab-abda)

- J7324 = Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm)

The JZ Modifier: A New Layer of Complexity

On July 1, 2023, CMS added another layer: the JZ modifier. This modifier must be added to claims when no drug is discarded during administration. Why? Because Medicare only pays for what’s actually used. If a vial contains 100 mg and you give 80 mg, you can bill for 80 mg. But if you throw away the remaining 20 mg, you can bill for the full vial-under certain conditions. The JZ modifier tells CMS: "I used every drop. No waste." If you don’t use it when you should, your claim gets rejected. If you use it incorrectly, you risk an audit. One gastroenterology practice reported a 30% increase in billing staff time just to handle JZ modifier documentation. It’s a small change, but it adds friction to an already complex system.What Providers Are Doing to Get It Right

Successful clinics have built systems to avoid billing errors:- Pharmacists verify the administered product against the billing code before submission

- Staff cross-check CMS’s quarterly ASP updates before billing

- Electronic health records are programmed with alerts when a biosimilar is selected

- Some practices use manufacturer-provided coding guides-Fresenius Kabi’s 2023 guide was rated "helpful" by 87% of surveyed providers

Why U.S. Adoption Lags Behind Europe

In the U.S., biosimilars make up about 35% of the infliximab market after five years. In Germany or the U.K., that number is 75-80%. Why the gap? It’s not just about price. It’s about how you pay for it. European systems often use reference pricing: all drugs in a class are reimbursed at the same rate-the lowest price. Providers get the same payment whether they choose the brand or the biosimilar. That removes the profit incentive to stick with the expensive option. In the U.S., the 6% add-on tied to the reference product’s ASP creates a financial wedge. Even when a biosimilar is 20% cheaper, the provider’s profit difference is still $30 per dose. That’s enough to influence prescribing habits, especially in high-revenue specialties like rheumatology and oncology. A 2020 analysis by MIT’s Dr. Mark Trusheim estimated that removing the reference product ASP from the biosimilar add-on could boost adoption by 15-20 percentage points.

What’s Next for Biosimilar Reimbursement?

CMS is considering major changes. In February 2023, it issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking asking for feedback on:- Replacing the 6% add-on with a fixed-dollar amount

- Eliminating the reference product ASP component for biosimilars entirely

- Implementing a "least costly alternative" (LCA) payment model

What Patients Should Know

Patients don’t need to understand HCPCS codes or ASP calculations. But they should know this:- Biosimilars are safe, effective, and FDA-approved

- They’re usually cheaper than the brand-name drug

- But your out-of-pocket cost might not reflect that savings

Bottom Line

Biosimilar billing isn’t broken-it’s just outdated. The system was designed to encourage competition, but it ended up protecting the status quo. Providers are stuck between wanting to save money for the system and needing to maintain revenue. Patients are caught in the middle, paying more than they should. The fix isn’t complicated: stop tying biosimilar reimbursement to the price of the brand-name drug. Pay providers based on what they actually give, not what’s on the shelf. Until then, the U.S. will keep paying more for biologics than any other country-and patients will keep wondering why the cheaper option isn’t more common.Do biosimilars have the same HCPCS code as the reference biologic?

No. Each biosimilar has its own unique HCPCS code, either a J-code (permanent) or Q-code (temporary). The reference biologic keeps its own separate code. For example, Remicade uses J1745, while Inflectra uses J7322. This change began in 2018 to ensure accurate payment based on each product’s actual price.

Why do providers sometimes prefer the brand-name biologic over the biosimilar?

Because Medicare pays providers 100% of the biosimilar’s ASP plus 6% of the reference product’s ASP. So if the reference drug costs $2,500 and the biosimilar costs $2,000, the provider earns $150 in add-on revenue from the brand and $120 from the biosimilar-a $30 difference per dose. In high-volume settings, that adds up. This structure reduces the financial incentive to switch, even when the biosimilar is cheaper overall.

What is the JZ modifier and why is it required?

The JZ modifier is required on claims for certain biologics and biosimilars when no drug is discarded during administration. It tells Medicare that the provider used the entire vial. If you don’t use the JZ modifier when appropriate, your claim may be denied. This rule, effective July 1, 2023, applies to drugs like infliximab and its biosimilars. It adds administrative work but helps prevent overbilling.

How often are biosimilar payment rates updated?

CMS updates biosimilar payment rates quarterly, based on the Average Selling Price (ASP) data submitted by manufacturers. The most recent update occurred July 1, 2023. Providers must check CMS’s Physician Fee Schedule updates every three months to ensure they’re using the correct payment amounts and codes.

Are biosimilars covered the same way by Medicare Advantage plans?

Not always. While Medicare Part B pays 106% of ASP for biosimilars, Medicare Advantage plans (Part C) can set their own reimbursement rules. Some pay 100-103% of ASP, others use formularies that favor the reference product. Patients may face higher copays for biosimilars even when they’re cheaper, so it’s important to check your plan’s drug list before treatment.

What’s the biggest barrier to wider biosimilar use in the U.S.?

The biggest barrier is the reimbursement structure itself. By tying the add-on payment to the reference product’s price, Medicare unintentionally rewards providers for choosing the more expensive drug. This creates a financial disincentive to switch, even when biosimilars are proven safe and cost less. European countries avoid this by using reference pricing, which pays the same for all drugs in a class-leading to much higher adoption rates.

Comments (9)

-

Kelly Gerrard December 30, 2025

Biosimilars are cheaper and just as safe but providers still push the expensive brand because Medicare rewards them for it. That’s not a market failure-it’s a policy crime. Fix the payment structure or admit you’re okay with patients overpaying.

Stop pretending this is about innovation. It’s about profit.

And no, 'clinical preference' doesn’t excuse financial coercion.

-

Henry Ward December 31, 2025

Let me break this down for the people still confused: the 6% add-on is a bribe. Providers make more money giving you the $2,500 drug than the $2,000 one. That’s not a bug-it’s the whole system. You think doctors care about your out-of-pocket? They care about their bottom line. The JZ modifier? A distraction. The real problem is that Medicare pays providers to choose the expensive option. End the ASP linkage. Now.

And don’t give me that 'patient safety' nonsense. Biosimilars have been used in Europe for over a decade with zero meaningful safety issues. This is pure rent-seeking.

-

Nadia Spira January 2, 2026

It’s a classic case of institutional path dependency. The reimbursement architecture was designed for a pre-biosimilar era where biologics were monolithic monopolies. The 2018 reform was a band-aid on a hemorrhage-individual J-codes introduced granularity but preserved the perverse incentive structure by tethering the add-on to the reference product’s ASP. The JZ modifier? A bureaucratic overlay that commodifies waste avoidance as a compliance ritual. What we need isn’t more codes or modifiers-it’s a paradigm shift to reference pricing. Europe doesn’t have this problem because they decoupled provider reimbursement from manufacturer pricing tiers. The U.S. is still stuck in a 1990s fee-for-service mindset while the rest of the world moved to value-based payment. Until we stop rewarding volume disguised as innovation, adoption will remain a political football, not a clinical imperative.

-

Kunal Karakoti January 2, 2026

I’ve seen this play out in my clinic. We switched to biosimilars because they’re cheaper and just as effective. But the billing team spent weeks retraining because the codes change every quarter. And the JZ modifier? We had to hire someone just to track vial usage. It’s not that we don’t want to use biosimilars-it’s that the system makes it harder than it should be. Maybe if CMS made the rules simpler, more places would follow.

Also, patients don’t care about ASP. They care if their copay goes down. Right now, it often doesn’t.

-

Glendon Cone January 3, 2026

Big thanks for laying this out so clearly 😊

As a nurse in a busy infusion center, I see this daily. We want to use biosimilars-we’re trained on them, we’ve seen the data. But when the billing team says 'hold on, this code doesn’t match the vial,' we lose 20 minutes per patient. And the JZ modifier? We had to print out a cheat sheet. It’s ridiculous.

But I’m hopeful. If CMS flips to LCA like MedPAC suggested, adoption could explode. Patients deserve this. Providers deserve to be paid fairly-not incentivized to pick the pricier option.

Let’s fix this. 🙏

-

Aayush Khandelwal January 4, 2026

Man, the U.S. healthcare system is a Rube Goldberg machine built by accountants with a grudge.

You’ve got biosimilars that are 20-30% cheaper, proven safe, FDA-approved-and yet we’ve got a reimbursement system that rewards the brand. The 6% add-on isn’t a subsidy-it’s a subsidy for inertia. And the JZ modifier? That’s like charging you for not spilling your coffee. It’s not efficiency, it’s over-engineered bureaucracy.

Europe’s reference pricing model? That’s the real innovation. Pay the same for all, let the market compete on price, and watch adoption skyrocket. Why can’t we just… do that?

Also, someone needs to tell the insurance companies that if the biosimilar costs less, the patient’s copay should too. But nope. They keep the difference. Classic.

-

Sandeep Mishra January 5, 2026

Hey everyone, I’ve been in this space for over a decade and I’ve seen how messy this gets.

First off-biosimilars are not generics. They’re not even close. But they’re safe. The FDA doesn’t approve them lightly. And the cost savings? Real.

But here’s the thing: the system isn’t broken because doctors are greedy. It’s broken because the rules were written by people who didn’t understand biologics. The 2018 change was a step forward, but the 6% add-on? That’s the anchor holding us back.

Let’s not blame providers. They’re just following the money. Let’s fix the money.

Reference pricing. Simple. Fair. Proven. Let’s go there.

And patients-if you’re on a biosimilar and your copay didn’t drop, ask your plan why. You’re owed that transparency.

-

Joseph Corry January 6, 2026

Let’s be honest: this entire discussion is a distraction. The real issue is that biologics are fundamentally uncompetitive by design. Biosimilars are not 'cheaper alternatives'-they’re regulatory compromises. The FDA’s 'highly similar' standard is a legal fiction. The 6% add-on is the only rational response to a market that can’t tolerate true price competition.

And let’s not pretend Europe is some utopia. Their systems are rationed. Their wait times are longer. Their innovation is slower. The U.S. pays more because it invests more-and that’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

Stop trying to turn biologics into aspirin. They’re not. And pretending they are is the real disservice to patients.

-

Colin L January 7, 2026

Look, I’ve spent 18 months auditing Medicare Part B claims for infliximab products across seven states, and let me tell you-this isn’t just complicated, it’s actively malicious. The JZ modifier alone generated over $2.3 million in denied claims in 2023, and that’s just one drug class. The fact that CMS doesn’t have a centralized, real-time code validation system is unforgivable. And the quarterly ASP updates? They’re published in PDFs on a server that crashes every third Tuesday. I’ve had providers submit claims using outdated codes because the CMS website was down during their billing cycle. This isn’t inefficiency-it’s negligence. The 6% add-on? It’s a relic. The reference product ASP should be excised entirely. Replace it with a flat 5% add-on, indexed to CPI, and call it a day. But no-instead we get a Kafkaesque maze of J-codes, Q-codes, modifiers, and vendor-specific coding guides that cost $1,200 a year to subscribe to. And we wonder why adoption is stuck at 35%. It’s not because doctors are stubborn. It’s because the system is designed to fail. And someone, somewhere, is getting paid to keep it that way.